Evolution and Paleobiogeography

Careful study and description of the incredible diversity of soft-bodied fossils from the Middle Cambrian of Utah over the last 30 years has permitted investigations of the broader evolutionary and paleobiogeographic contexts of these remarkable fossils. Especially imporant descriptive work includes the research of:

- Robison & Richards (1981): Bivalved arthropods

- Conway Morris & Robison (1982): Jaws of Anomalocaris

- Briggs & Robison (1984): Nontrilobite arthropods and Anomalocaris

- Robison (1984): Naraoia

- Robison (1985): Lobopods

- Conway Morris & Robison (1986): Priapulids

- Babcock & Robison (1988): Hyolithids

- Conway Morris & Robison (1988): Soft-bodied animals and algae

- Robison & Wiley (1995): Meristosoma

- Briggs et al. (2005): Vetulicolians

- Cartwright et al. (2007): Jellyfish

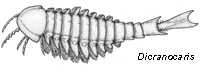

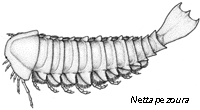

- Briggs et al. (2008): Arthropods, including new genera Dicranocaris & Nettapezoura

Exploring the evolutionary and paleobiogeographic context of this documented diversity has been the focus of significant research in recent years in the Division of Invertebrate Paleontology at the University of Kansas. This research was supported by National Science Foundation Grant EAR-0518976.

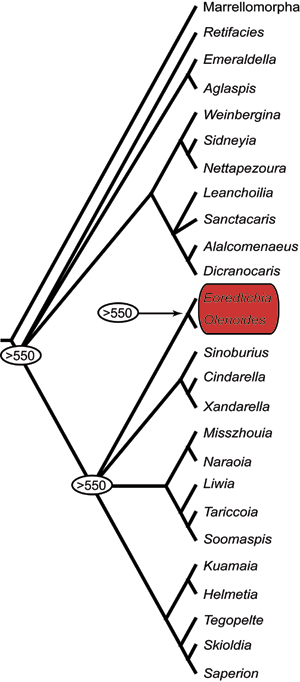

One of the major goals of this research was to resolve the relationships of arachnomorph arthropods. In particular, cladistic methods were used to explore the relationships of two new genera from the Middle Cambrian of Utah, Dicranocaris and Nettapezoura to previously described species from other deposits, including the Burgess Shale and Chengjiang soft-body faunas (see Hendricks & Lieberman, 2008).

One of our results is shown to the right (Hendricks & Lieberman, 2007, fig. 3). Besides identifying Sidneyia as the sister taxon (i.e., closest relative) of Nettapezoura and Alalcomenaeus as the sister taxon of Dicranocaris, this research demonstrates that trilobites (group in red) are evolutionarily derived arachnomorphs. This suggests that many other arthropod groups known only from soft-body deposits must be at least as old, if not older, than trilobites, a group which had likely diverged before 550 million years ago.

After this phylogenetic analysis was completed, the branching order of the tree, in conjunction with biogeographic information, was used to study the role of continental breakup in driving the observed patterns (see Hendricks & Lieberman, 2007). This research found that cyclic environmental events such as sea-level change, as well as the dispersal ability of the animals themselves, were likely responsible for the observed evolutionary patterns.

A second approach to studying paleobiogeographic in soft-body fossils has involved using geographic information systems (GIS) and models of ancient paleogeography to compare distributional patterns in trilobite and non-trilobite arthropod species using a newly compiled database derived from literature and museum sources (work by Hendricks, Lieberman and Stigall; for publication click here). Surprisingly, this research has shown that soft-body arthropod species were, on average, more widely distributed than trilobites.